by Joe Benevento

Anyone familiar with mystery knows the “femme fatale,” a character who can prove literally lethal to the man she seduces away from clear thinking. Bridget O’Shaughnessy in Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon is an example, presenting herself as a “damsel in distress” in need of Sam Spade’s help and protection, but ending up his ultimate distraction and potential demise (see the character played by Jane Greer in the 1947 noir film, Out of the Past for another classic rendition of the type.) In spite of our familiarity with the function of a femme fatale, not all readers or writers of fiction realize how far-reaching the concept is, how flexible, and how ultimately crucial it can be to any plot involving the kind of thinking needed to unravel a complex crime.

Anyone familiar with mystery knows the “femme fatale,” a character who can prove literally lethal to the man she seduces away from clear thinking. Bridget O’Shaughnessy in Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon is an example, presenting herself as a “damsel in distress” in need of Sam Spade’s help and protection, but ending up his ultimate distraction and potential demise (see the character played by Jane Greer in the 1947 noir film, Out of the Past for another classic rendition of the type.) In spite of our familiarity with the function of a femme fatale, not all readers or writers of fiction realize how far-reaching the concept is, how flexible, and how ultimately crucial it can be to any plot involving the kind of thinking needed to unravel a complex crime.

Some detectives avoid the danger of a femme fatale by staying away from any relationship with any woman. The list of detectives who are mistrustful of entanglements with females is a long and illustrious one. I still am surprised at how many female readers (my fifteen year old daughter among them) are huge fans of Sherlock Holmes, since Holmes himself is no fan of women. In The Sign of Four, in response to Watson accusing Holmes of being “an automaton….inhuman” because of his disinclination to notice the charms of a woman who has come to them for aid, the detective notes: “It is of the first importance not to allow your judgment to be biased by personal qualities…. The emotional qualities are antagonistic to clear reasoning.” Much later in the novel he is blunter: “”Women are never to be entirely trusted, not the best of them.” Another very popular detective, Nero Wolfe, explains to his employee Archie Goodwin, why he prefers him over a spouse: “to have you with me …is always refreshing because it constantly reminds me how distressing it would be to have someone present- a wife, for instance- whom I could not dismiss at will.” (Fer-de-Lance). Even a married detective among the bunch, Nick Charles in Hammett’s The Thin Man is retired from detective work before he marries Nora and accidentally re-involved when he reluctantly gets thrown into a new murder investigation; crime solving and domestic life do not mix in classic detective fiction. Holmes and Wolfe simply avoid women, Sam Spade or Chandler’s Philip Marlowe get involved with femme fatales, but are wary enough not to be undone by them.

Of course this mistrust of women and particularly their sexuality can probably be traced all the way back to the Garden of Eden and the attempt to blame Eve for Adam’s own bad decision making. In fact, Umberto Eco in The Name of the Rose, codifies this tradition for all readers of mystery when he has the monk Ubertino explain to the young narrator why a woman falsely accused of witchcraft is still essentially guilty: “If you look at her because she is beautiful and are upset by her… if you look at her and feel desire, that alone makes her a witch.” Eco’s novel , set in medieval times, reveals the femme fatale as a by-product of men’s own misplaced carnal desires.

The idea of always making a woman the threat to a detective’s equilibrium has become not only tired but also distasteful to a large portion of the reading public, so mystery writers have made adjustments. Sue Grafton is one of the most popular writers of contemporary detective fiction. (She’s presently all the way up to W in her letter by letter mysteries featuring female detective Kelsey Milhone). It is far from coincidental that in her very first book, A Is for Alibi, her detective finds herself entangled with a suspect-become -lover, who essentially serves as her “homme fatal.”

While having a male equivalent is one way to freshen the trope, sexual distraction is not the only option, as a detective can be dissuaded from clear thinking and concentration by a variety of factors: say, his or her checkered past or an ongoing drinking problem. For example, Jim Chee in Tony Hillerman’s very successful novels set in Navajo territory not only is sometimes distracted by his various romances, but also by his devotion to Navajo culture, which more than once collides with his ability to concentrate on the case at hand. In A Thief of Time, for example, Chee is less than methodical in his investigation of a crime scene because the proliferation of human bones at the site makes him want to flee because of their especially threatening values within his religion.

Still, while writers like Conan Doyle and Rex Stout got around the femme fatale by having their heroes be immune to her, if you are presenting your protagonist as a “normal human being,” you are going to have to address the question of relationship and how it will affect your hero’s ability to detect. In Lehane’s Mystic River, Sean Devine’s distraction is the wife who cheated on him and left him. Interestingly, though it is the wife who has been unfaithful, eventually the husband seeks forgiveness, and mostly because we are asked to understand that his attempts to be a traditional tough, emotionless cop are what ruined his relationship with his wife in the first place. The blame is no longer placed on the woman for attracting the man but on the man for his attempt to be emotionless.

In creating a detective it isn’t only important to show how he or she is smarter or stronger or more resourceful than most others, but also what his or her “femme fatale” may be, what weakness, what bias, what attraction that challenges the ability to detect. Even Holmes and Nero Wolfe are not immune to this rule; though women cannot seduce them, Holmes has a problem with cocaine and Wolfe a strong disinclination ever to leave his home. And while we have graduated from Holmes’s categorical dismissal of all women, no protagonist, however brilliant or tough or idiosyncratic, will be fully compelling without a weak point, a humanizing characteristic to challenge that considerable ability.

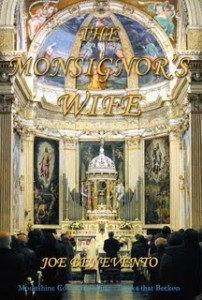

Joe Benevento’s first mystery novel, and ninth book of poetry and fiction overall, The Monsignor’s Wife, came out in September of 2013 with Moonshine Cove Publishing. For more information go to:www.AuthorJoeBenevento.com

Joe, thanks so much for guest posting today. I love your ideas for putting a modern twist on the femme fatale trope by providing alternate distractions/weakness for sleuths. As with all fiction, I think it’s the protagonist’s *weakness* that makes him or her appealing and real to readers. I know for one of my series, my sleuth’s weakness is her own hubris and somewhat childish desire to show off. Thanks for this food for thought for mystery writers…and writers of other genres, too.

Thanks to you, Elizabeth, for having me back. Yes, in my own mystery writing, my protagonist, Tony Cupelli, definitely has some weaknesses, too many in fact, for some people’s taste, but, happily, he’s still finding his way, plus there’s lots of room for redemption in subsequent novels featuring him.

Women are the greatest distractions, but there are other things in life that can cause fuzzy thinking.

Yes, Alex, I agree, of course; in fact, some people don’t need any distraction to think poorly, but a detective, we most often assume, has some ability to win the day if he or she does not get thrown off course.

Elizabeth – Thanks for hosting Joe.

Joe – You’ve given some good examples of the femme/homme fatale here. And I agree that that sort of character can provide an effective distraction for a sleuth. As you point out, it’s important to not to make her/him a caricature, but it certainly has worked effectively.

Yes, Margot, we’re dealing with that very issue in the Mystery class I’m teaching at Truman State right now. Many of the students are not familiar with the “femme fatale” idea and are finding it a little distasteful as it is rendered in writers like Hammett and Chandler. I’d argue, though, that the Sternwood sisters in The Big Sleep or Bridget in The Maltese Falcon, are fleshed out enough not to be stereotypes.

Joe, this is an insightful article. I never thought to call a protagonist’s weakness a “femme fatale,” but now that you have, it makes perfect sense. As a reader and amateur student of psychology, I think we tend to relate to fictional characters (and real humans) through weakness, failure, and rejection, primarily because everyone has failed and been rejected. (See any successful stand-up comedian for examples). Too, if a character is not weak/flawed in some way, where is the tension? How else can a writer develop conflict and layers of characterization?

Thanks again.

Right, Max- well said.

Joe–thanks for a thoughtful–and useful–examination of an important motif in crime fiction.

Like Max Everhart, I especially like the way you expand the femme fatale idea to include anything that works to seduce the protagonist–booze, cocaine, demons from the past, etc. This is very helpful. When I apply it to my own work, I see that the back story for my heroine (is that now sexist, like actress?) reveals a homme fatale, in the person of her father who died when she was thirteen. Dealing with this trauma is an ongoing, distracting challenge for her. It weakens her, until she is at last able to come to terms.

Thanks for your thoughtful comment, Barry. The important thing is to keep in mind as we write how boring a detective would be if he or didn’t have some near-fatal flaw to keep it all from being too predictably certain that the protagonist will prevail.

Fabulous article full of useful tips for writing a femme fatale and not a caricature. You’ve given some excellent examples. I have a few to add, some classic and a few from more recent films. What about Bonnie Parker ( Bonnie & Clyde)? Some of my other favorites include: the woman from Double Indemnity , Maddy Walker/ Body Heat, Cora Smith/ The Postman Always Rings Twice, Lynn Bracken/ L.A. Confidential, Laura Mannon/ Anatomy of a Murder, the character that Kim Novak played in Vertigo. Now for some more recent ones. The character that Sarah Michelle Gellar plays in Cruel Intentions, the female character in the movie starring Denzel Washington, Out of Time, Katherine Trammel from Basic Instinct, Alex Forrest in Fatal Attraction, Demi Moore in Disclosure, Neve Campbell ( and her co-star, whose name I cannot think of, but who was actually worse than the character played by Campbell) in Wild Things. That’s about all I can think of right now, but I’ve always been a fan of femme fatale films. You are so right about women being a distraction, just ask any many doing hard time in prison who had a female co- conspirator who is in the free and clear. Loved your post.

Thanks so much, Melissa. Yes, the word limitations of a blog prevented me from giving more examples, so I appreciate your having listed some great ones, and in so doing letting us see how the trope is still alive and well to the present time, in spite of so many other changes in societal mores and expectations.

Oh lot’s of food for thought there Joe. Thanks for that. I think we all search for the weakness in our protags immediately, before anything like plot. We need to relate to care. This is very useful. :)

shahwharton.com

Thanks, Shah. I think you’re right, though my main character in “The Monsignor’s Wife,” has, if anything, been too flawed for some people’s taste, though I’m happy to say that seemed more a problem with some agents and publishers than it has with the majority of readers.