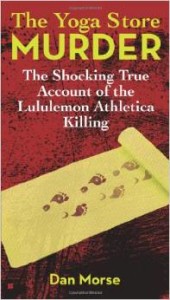

By Dan Morse, @morsedan, author of The Yoga Store Murder

In 2011, as a reporter for The Washington Post, I covered the most violent of murders in the least likely of places. Someone had slashed, stabbed and struck Jayna Murray more than 331 times in the back of a high-end yoga store. The killer used more than six weapons, including a hammer, wrench, knives and a jagged steel bar used to display merchandise. That dichotomy – complete mayhem in a place of peace and Zen – got me thinking about writing a book about the case.

To pull readers along for 300-plus pages, though, I needed detailed scenes that not only advanced the plot, but also built out very real characters. After all, readers of non-fiction are like readers of mysteries; they want to get to know people as they turn each page.

To write such scenes, I first laid a foundation of detailed reporting. I got some good breaks. I was able to read 11,000 text messages pulled from the killer’s phone, which offered direct dialogue and candid thoughts. I conducted repeated interviews with detectives – at police stations, bars, and back patios. Those characters formed the core of the book – the killer and the cops. I also spent a lot of time with Jayna Murray’s family, who helped me understand Jayna and how devastated the murder had left them.

During one interview, David Murray, Jayna’s dad, started speaking about the last time he’d seen his daughter alive. He lives in Houston, and was staying at Jayna’s condominium just outside of Washington DC. In my mind, I saw David’s story going to a place that could be easily conveyed in a scene: Jayna driving David to the airport, the two of them going inside and lingering before take-off. But that’s not what happened. On the morning David was to leave, Jayna had a lot of packing to do for a planned trip to a wedding. So David took the subway to the airport. It was only later, when I wrote the scene, that I had one of those oh-yeah-that-axiom-again-forehead-slapping moments: The truth is almost always more interesting than what writers hope the truth to be. And it’s that nuanced truth that builds out characters.

In this case, as readers of the book were starting to know by page 120, David and Jayna were strong, independent people. David had served as a Special Forces officer in Vietnam, then gone on to manage oil drilling sites around the world. Jayna went bungee jumping to celebrate her 30th birthday, and was two months shy of getting her MBA and pursuing a career in corporate marketing. The two were so close they didn’t need drawn-out goodbyes – they’d be on the phone soon enough, seeing each other again soon enough. A parting that was understated seem to fit them.

So here is how I closed out that scene, picking up from the day before, when the two had met in North Carolina so they could see off Jayna’s brother Hugh, who was being deployed to Iraq. David took the occasion to spend some extra time with Jayna.

He drove back with her to Washington – just the two of them, talking in her car while driving north. Subjects swung from politics to pacifism to David’s questions about the principles of marketing as they applied to specific business projects. “Why do you say it that way?” he’d ask. David could sense Jayna’s fears for her brother Hugh. They were well-placed: Iraq was chaotic, even if it was no longer at war. And her brother would be moving around, the most dangerous thing to do there. David, of course, knew all about combat. “Hugh is going to be fine,” David told his daughter.

Time was ticking on their visit. As they got into Washington, David drove Jayna by a friend’s house so she could pick up a bridesmaid dress. The two planned to get a few hours of sleep before their flights the next morning – David back home to Houston and Jayna to Minnesota, for a wedding. But when it was clear Jayna needed more time to finish packing that morning, David said he didn’t need a ride to the airport. He hugged his daughter good-bye. “I love you,” they said to each other.

David walked out of the condo and two blocks to a subway stop. It was January 20, 2011, and the last time he’d see his daughter.

give sports-writing a go at the campus newspaper. It proved a better fit. In his junior year, he tried out for the football team – going on to write a year’s worth of columns chronicling his trials, tribulations and deep bruises as a slow but poor route-running wide receiver. After graduation, Morse combined his engineering degree with writing and, as if it had been well-planned, took a position at Civil Engineering magazine in New York. Who among us can forget his prescient 1989 piece on waste-water treatment disposal regulations: “Sludge in the Nineties.”

give sports-writing a go at the campus newspaper. It proved a better fit. In his junior year, he tried out for the football team – going on to write a year’s worth of columns chronicling his trials, tribulations and deep bruises as a slow but poor route-running wide receiver. After graduation, Morse combined his engineering degree with writing and, as if it had been well-planned, took a position at Civil Engineering magazine in New York. Who among us can forget his prescient 1989 piece on waste-water treatment disposal regulations: “Sludge in the Nineties.”Wanting to know how other things worked – crime, politics, business – Morse sought a reporting position at more than 50 newspapers. Exactly one of them offered him a job, The Alabama Journal, an afternoon daily in Montgomery, Ala., where Morse settled in as a cops reporter. He moved on to that city’s morning paper, The Advertiser, covering state politics and becoming a Pulitzer Prize finalist for stories on the Southern Poverty Law Center. From there, he moved to The Baltimore Sun, The Wall Street Journal, and, in 2005, The Washington Post. (Some of his favorite stories, and the most interesting people he has met, can be viewed here.)

Morse grew up with four siblings in Urbana, Ill., where his parents still live. He is married to Dana Hedgpeth, a fellow Post reporter. They have a daughter named C.C.

So you turned the details of a real murder and the people involved into a story? Is the murder just a grisly? (Because you’re right, you can’t make that stuff up.)

Hi, thanks for reading and commenting … I reported the story for the Post, and then decided to write a book about the case. I had to report a lot of new material for the book, and re-reported earlier ground I’d covered. I was trying to understand what happened, but much more importantly, who the people/characters were.

Elizabeth – Thanks for hosting Dan.

Dan – I think you’ve hit on something that’s really important in writing: making characters accessible. In your case you had real people whose lives you wanted to convey. And you certainly did the research to evoke those characters effectively. I think that kind of research helps in creating fictional characters too.

Dan, by being able to interview the family members, etc., you were able to give more depth to your characters. From a reader’s point of view, this brings the characters to life for me. It makes me feel the pain and heartache of the victim’s family, the emotions the cops felt handling the case, and even a glimpse at what the killer was thinking or feeling. You definitely made the characters accessible.

Elizabeth, thanks for the introduction to Dan.

Thanks very much. It was an emotional case for everyone who touched it. Even the medical examiner and autopsy technician, who do autopsies all the time at Maryland’s state forensics lab in Baltimore, found themselves getting upset over what they saw. The technician, Mario Alston, couldn’t remember another murder so horrific — and found himself struggling to get it out of his mind when he came home. It’s those kind of personal insights I tried to bring to the book — to make it go beyond just the horror of the murder.

You had access to people that most don’t and that added a lot to the story I’m sure.

Thanks for posting today, Dan!

I think text messages from the murderer’s phone would be incredibly useful for the true-crime writer–as you say, direct dialogue. That would really help the story come alive for readers.

Thanks for the post-space! And yes, the text messages were very helpful in showing both sides of the killer — the one other people saw and the hidden, secret life.

Weaving all the details of the truth into a story that will have people turning pages isn’t easy. Sounds like you did a great job!

Your great attention to detail makes for a great read. Definitely the contrast of a grisly murder in a place of peace caught my attention. I don’t s’pose you’ll tell us “who dun it”, eh? Best wishes.